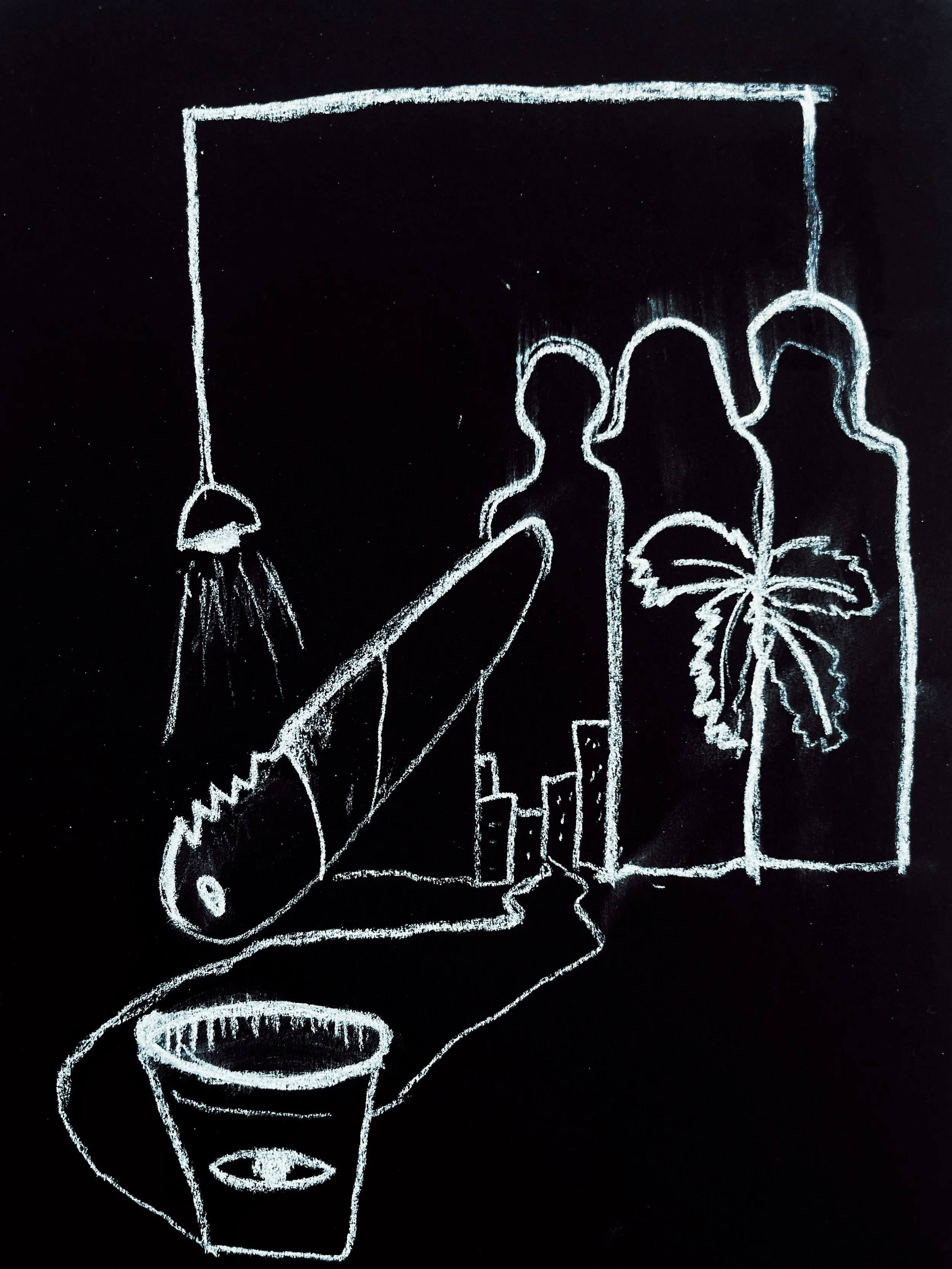

The Void and The Unconscious. : A Journey Through Pain and Memory.

I believe there are moments in life when pain transcends its physical boundaries and becomes a mirror to something deeper.

The Paradox of the Void

The void is often depicted as a paradoxical realm. A space where everything and nothing coexist. It is both empty and full, a place where absence and presence merge into an endless cycle. Commonly associated with loss, solitude, and darkness, the void is an elusive space that is neither completely unknowable nor fully understood. It holds within the tension between knowing and unknowing, between light and shadow, between being and non-being. It is, in a way, a place of potential, where what is and what could be intermingled, awaiting revelation.

Darkness, Memory and the Unconscious

In a similar way, darkness has long been a symbol of the unconscious mind. It is where thoughts, feelings, and memories (especially those repressed) find their way into our awareness. Darkness often manifests itself in the form of images and emotions that are simultaneously frightening and unrecognizable, representing the unknown elements of our psyche. Here, in the recesses of our unconscious, lies the void of unprocessed experience, awaiting interpretation. And yet, as the void knows only the silence of its vastness, so too does darkness speak to us in a language of obscurity.

But what if this emptiness, this darkness, holds more than just the unknowable? What if the truth is, in fact, as empty as the void? The truth, in this way, does not shrink under pressure; it is not defined by external circumstances, nor does it succumb to the limitations of perception. It is the one constant that remains unchanged amid the flux of reality. Truth is not swayed by distortion or fear; it can take on many forms, filling the void without ever losing its essence. It stands outside of time and space, transcendent and eternal. In this context, the truth is the one constant in a world filled with uncertainty.

The Role of Memory in Understanding the Self

In the dance of consciousness, memory plays a crucial role as the keeper of truth. Memory does not simply record past events; it actively shapes our understanding of who we are and who we might become. It acts as the bridge between the known and the unknown. Through memory, we can access the deeper layers of the self, those parts of us hidden beneath the veil of conscious awareness. Memory in this sense, becomes a map of the soul allowing us to travel between the past and the present, the conscious and the unconscious.

I have come to understand that, memory is not enough on its own. It requires consciousness, the awareness that allows us to make sense of and integrate the fragments of past experiences into a cohesive narrative. Without consciousness, memories would remain disjointed and disconnected, like pieces of a puzzle that have yet to find their place, so memory and consciousness are intimately intertwined: memory provides the content, and consciousness gives it meaning. They are not separate; rather, they are two sides of the same coin, each dependent on the other for the formation of a coherent sense of self.

Confronting the Unconscious for Healing

But as we seek to understand the self, we must also confront the unconscious. The unconscious is the repository of those experiences we have chosen to forget, to bury deep within the folds of our psyche. But these repressed memories do not disappear, they are like cockroaches surviving the hells of any environment. They continue to exert influence, guiding our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in ways we may not fully understand. Engaging with the unconscious is essential for healing and growth. Just as darkness hides truth in the shadows, so too does the unconscious obscure the fullness of who we are. Yet, it is in these forgotten spaces that the true work of self-integration happens.

Chemical and Biological Forces Within Us

At this juncture a question arises : Are we truly acting according to our soul’s free will, or are we simply slaves to the chemical processes that govern our bodies?

In this metaphorical framework, I think of the synaptic gap as a crucial symbol for the transfer of knowledge between the layers of consciousness and the unconscious. The gap serves as a bridge, much like memory itself, carrying neurotransmitters, chemical messengers across synapses to convey information. It is in this space that the flow of consciousness intersects with the body by translating thought into action, understanding into behavior. The synaptic gap, therefore, is not merely a biological component; it is a conduit for truth, transmitting knowledge from the deeper layers of the unconscious to the awakened mind.

This fear of being reduced to mere biology opens up a larger existential dilemma: Are we more than the sum of our chemical reactions, or is it our fate determined by biology alone? It is a question that lies in the intersection of philosophy, psychology and neuroscience.

The Weird Paradox of Forgetting and Healing

If we understand memory as the pathway to both self-knowledge and spiritual awakening, then it follows that the integration of memory is the process by which we come to understand the truth of our existence. Memory is not merely a passive record of events; it is the very fabric of who we are. As the soul cannot exist in forgetfulness, memory anchors us to our true essence, offering us the chance to transcend the ego and experience life more authentically. This process of integration is not just psychological; it is spiritual.

Forgetting, paradoxically, plays an equally vital role in this process. It is not merely the absence of memory but a selective mechanism that allows us to detach from experiences that no longer serve us. The act of forgetting, far from being a loss, is a necessary function of psychological survival. However, if we forget too much, if we fail to engage with the memories that have shaped us, we risk becoming emotionally stagnant. To achieve true integration, forgetting must be balanced with remembering. The dynamic tension between remembering and forgetting is what allows us to grow.

The concept of oblivion plays a paradoxical role in the healing process. It is often through a form of forgetting or loss of self that recovery begins.

At the height of my addiction, I was lost to myself, living in a state of oblivion. This loss, however, created space for deep contemplation of the internal processes taking place within my mind. It is in the emptiness of oblivion that we can begin to rebuild, to create anew from the fragments of who we were. Tedeschi and Calhoun’s (2004) work on post-traumatic growth suggests that forgetting, or the dissolution of the old self, provides a fertile ground for new growth. Through this period of oblivion, I shed the layers of one found identity, with the lies, the false constructs and the addictions that had defined me for so long. This shedding was not a loss but a necessary part of the healing journey that felt extremely uncomfortable all throughout . The “I” that emerged was not the same as the one who entered the darkness, but it felt stronger yet lighter in the bones, more authentic, and with a strange feeling of alignment. The act of forgetting, therefore, is not an act of abandonment but of transformation, offering a blank canvas upon which the self can be redrawn.

The Role of Memory in Post -Traumatic Growth

In recovering from trauma, the process of reconstructing one’s narrative is essential. Memory serves not only as a record of past events but as a foundational element in the creation of identity. In my own healing journey, it became clear that recovery is as much about reshaping the past as it is about living in the present. Rewriting my personal narrative allowed me to take ownership of my experiences and, ultimately, to reclaim my sense of sovereignty. Which is kind of hilarious to even say since Im 22 and whatever I think I am now, I might later not be. Either way it is important to give the work its recognition. This act of narrative reconstruction is aligned with the work of Smith and Sparkes (2008), who argue that the self is continually reformed through storytelling, and in doing so, we recover not just our memories but our lives.

Through this process of memory integration, we not only confront the self but also begin to see the world more clearly. The integration of memory is the path to spiritual awakening. It is through the process of remembering through the return to the self that we achieve a higher state of consciousness, one that allows us to transcend the limitations of the ego and experience the world in its truest form. As Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote, “The only journey is the one within.” This clarity of perception, when combined with the soul’s deepest truth, allows us to engage with the world in a way that is not filtered by past wounds or future fears.

Obviously I rely on personal experience when speaking about this. In my search for understanding the nature of consciousness, memory, and the concept of the soul, I had an unexpected guide: the suffering from hungover or withdrawal. Though it sounds like not much of a big deal, in my case it was. After a reckless binge on alcohol, when my body and mind felt irreparably broken, I began to see the delicate interplay between mind, memory, and emotion. The experience was intense and uncomfortable, it became not just a physical ordeal but an awakening to deeper truths about how I perceived reality and, ultimately, how I understand my place within it.

The journey that led to this revelation began in the immigrant’s liminal space. Coming from Cuba, my sense of self was already fractured. I had long been caught between two worlds, the culture I left behind and the one I now lived in, never fully belonging to either. The details of my life in Cuba faded from view, overshadowed by the immediate need to fit in, to adapt to a world that felt alien. I became a chameleon, crafting a new identity to blend into the landscape of high school and beyond, but the insecurities that traveled with me from Cuba remained embedded in my responses to others. This dissonance in identity became a central theme in my life, and with it came a growing sense of not belonging, of always feeling behind, disconnected, as though I were somehow losing touch with who I truly was.

By the time I graduated, my early days of this self-imposed exile began, agitated between family expectations and my own identity crises I had stumbled into a reckless rebellion against the norms I couldn’t quite grasp. The rebellion was not just a defiance of societal rules but a desperate attempt to escape the unbearable weight of my internal contradictions. So I turned to drugs like psychedelics, but, primarily alcohol as a way of coping. However, I soon found that the substances that offered temporary relief also carried with them a profound side effect: they blurred the lines between memory and reality, creating a distorted sense of self that felt neither authentic nor whole. This disconnection, initially small, deepened with each use. It was during one particular binge that I was forced to confront a truth I had been avoiding.

There is one particular experience that shook me enough to set the fire of my curiosity. It happened the day after the night I spent consuming an entire bottle of whiskey, I woke up the next morning to intense physical pain. As I sat in the bathroom, throwing up what felt like nothing but emptiness, the pain began to travel. It moved from my stomach, where it had first manifested, to my head, where a headache began to throb relentlessly.

My body, now a prison of sensation, felt both heavy and weightless at the same time, as if I was stuck between worlds: the world of the living, where my body ached, and the world of the dead, where my mind was trapped in a loop of regret and self-loathing. I closed my eyes, hoping for respite, but instead, I was met with images distorted faces, fast motion movements, screams, disturbing and violent scenes that repeated on a loop and places that felt at once familiar and utterly foreign. Also some I had long repressed and others I had forgotten. Memories of my mother’s disappointment over my lack of success in the United States resurfaced, intensifying my shame. I tried to make sense of it, to grasp some meaning from the chaos, but the images kept shifting, ever-elusive. It was as though my mind, overwhelmed by the flood of memories and sensations, was no longer able to distinguish between what was real and what was imagined. I had become lost in a labyrinth of my own making, where time had no meaning and the self was fragmented into a million pieces. The fear I felt in that moment was not just a fear of physical death, though that seemed imminent. It was a fear of existential dissolution, the fear of losing my connection to everything I had once known, of fading into a state of nothingness. In that moment of suffering, I began to question the very nature of memory itself.

This experience was a reflection of something much larger than myself. It was a moment where memory, consciousness, and the soul collided, where the weight of past experiences and the turbulence of the present moment merged into a singular, overwhelming truth. The journey toward understanding my existence, toward integrating my fragmented self felt like a permanent trip to the Void.

Memories are often seen as static records of past events, fixed and immutable. Yet, memory is not a simple snapshot; it is dynamic, shaped by emotion and perception, constantly evolving over time. Memories are filtered through the lens of present experiences, reshaping the way we remember the past. This realization prompted me to consider whether consciousness itself operates in a similar way, fluid and subject to change, shaped by our ongoing engagement with the world around us.

The Fluidity of Memory and the Impact of Trauma

According to Bessel van der Kolk (2014), trauma disrupts the mind’s ability to form coherent, integrated memories, often resulting in disjointed fragments that resurface unexpectedly. These fragmented memories shape not only our emotional responses but also our perception of identity.

Philosophically, this fragmentation challenges the traditional notion of a stable identity. Identity, as philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1991) states, is constructed from narrative a continuous thread of memory that gives coherence to who we are. However, trauma interrupts this thread, example, poverty in Cuba made me feel weird about holding american dollars, and I dwell in overspending because otherwise I would feel anxious, which led me to question if identity is permanent or something constantly rewritten in response to experience.

What if consciousness isn’t a fixed, singular entity? What if it, like memory, is a dynamic force that interacts with external stimuli and internal experiences to create our subjective sense of reality? The more I considered this, the more I realized that consciousness is not something we merely experience passively; it is something we actively engage with. Our minds don’t just receive information; they process and reinterpret it, shaping our perception of the world and ourselves.

The pain I felt that morning, the guilt, and the emotional turmoil, were not merely the result of a hangover. They were an externalization of the dissonance within my mind the conflict between who I was and who I had been trying to become. The experience illuminated the way memory, consciousness, and identity are intricately connected. It became clear that our perceptions of reality are shaped not just by our external environment, but by the internal narratives we construct. These narratives, informed by our memories, emotions, and experiences, become the lens through which we view the world. What struck me next was the profound connection between the mind and body. The physical pain I experienced in my hangover was inextricably linked to the mental anguish I was feeling. It was as if my body had internalized the emotional chaos of my mind. This connection raised further questions: If the mind and body are so deeply interconnected, then what role do the physiological processes in the brain such as neuron activity, neurotransmitter release, and synaptic communication, play in shaping our perception of reality? Could it be that consciousness, in its entirety, is not just a psychological or philosophical concept, but also a biological process, intricately linked to the functioning of our neural networks?

Neuroscience suggests that our perception of reality is largely influenced by the neural activity in our brains. The brain doesn’t just receive sensory data from the environment; it actively interprets and makes sense of it, creating the subjective experience of the world around us. The neurotransmitters that govern mood, perception, and thought patterns play a crucial role in how we process and react to these external stimuli. In this way, consciousness can be seen as a biological phenomenon, deeply tied to the physical processes occurring in the brain. This realization that our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions are not isolated from our biology, helped me understand that consciousness is not just an abstract philosophical concept, but an ongoing, ever-changing process that emerges from the intricate dance between our mind and body.

Written on December 10th, 2024

Bibliographical References:

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters to a Young Poet. W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge.